Explained: Downforce, Slipstream & Dirty Air

Photo: Jose Izquierdo Galiot

“Slipstream” and “dirty air” are two terms that are often used in the context of high-downforce, open-wheel racing, but rarely outside of it. Moreover, the terms can often confuse those new to motorsports because both deal with the same thing: the effect that air passing over a car has on the car behind it.

Before we get into explaining slipstreaming and dirty air, however, we need to start with the basics. Keep in mind the explanations below are very simplified. They’re meant to give you an idea of the concepts rather than to be completely scientifically accurate.

Aerodynamics are Sensitive: Even a bit of dirt can affect them – so here’s how to detail your car like a pro

Downforce

Automakers as a whole have been talking about aerodynamics a lot more in recent years, in large part because aerodynamic efficiency is a good and relatively cheap way of increasing fuel economy. There are many types of aerodynamic mechanisms, but we’ll be talking about just one in particular for this article: downforce.

Downforce can be somewhat simplistically explained as what happens when air passes over a car and pushes it toward the ground. This increases the vertical force on the tires and consequently generates more grip. Specific aerodynamic designs can increase or decrease downforce and even focus it in certain places, usually at the front or rear of a car via wings and spoilers.

Formula 1 cars, with their complex bodywork and wings, famously produce so much downforce that they could theoretically drive upside down at high speeds. In other words, the force with which the air pushes the car down is so great that it exceeds the weight of the car itself.

However, there are downsides to downforce. For example, it isn’t as effective at higher altitudes because the air is thinner—such as at the Mexican Grand Prix. Furthermore, high downforce causes aerodynamic drag, or air resistance; while the car is trying to go forward, the air is pushing it down instead, thus decreasing its top speed.

One of the difficult aspects of setting up a car for a race is to balance it on that fine line where it has enough grip for the corners but doesn’t lose too much speed in the straights.

Slipstream

Now that we understand the basics of downforce, it becomes very easy to understand the concept of slipstreaming. The more downforce a car produces, the more it is slowed down in a straight line when driving in open air, and thus the more it benefits from being in the wake of another car—aka their slipstream.

When two cars are closely following each other, the one in front gets the brunt of aerodynamic drag while the one in the rear enjoys a brief window of reduced drag—and thus higher speeds. To make an analogy of it: imagine that you are running a race but the wind is against you. If something were to block the wind, you would suddenly be able to run even faster thanks to the reduced resistance.

It’s the same thing in motorsports, and the closer a driver is to the car ahead, the bigger the effect. It’s simple, it’s effective, and it’s one of the major ways open-wheel racing drivers get past each other. But it only works in a straight line.

Basic Car Maintenance Routine maintenance tips and schedule

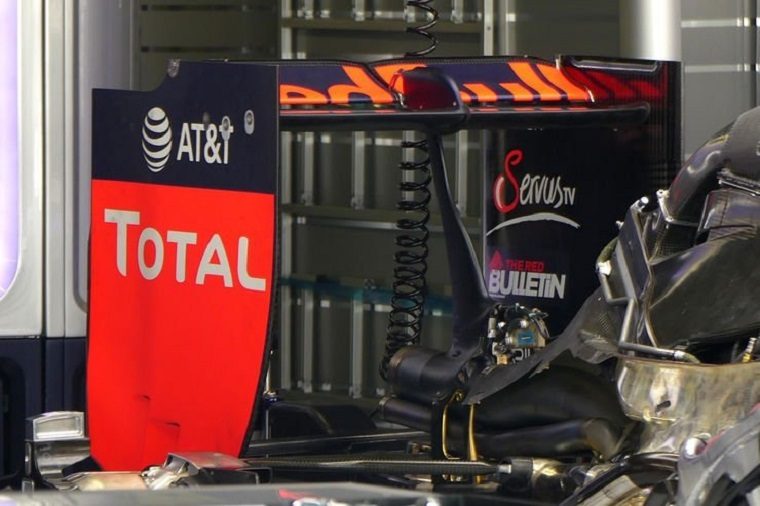

A rear wing set for low downforce to prepare for the high-speed Italian Grand Prix in Monza

Dirty Air

Dirty air is a little more complicated and a phenomena primarily contained within Formula 1, simply because of the sheer levels of downforce involved.

A consequence of F1 cars’ clever aerodynamics is that they create a region of extremely turbulent air behind them, otherwise known as “dirty air.” When an F1 car closely follows another while in that area of dirty air, which usually occurs when the gap ahead is down to a little under a second, its own aerodynamic wizardry is compromised.

This leads to a significant reduction in downforce, which—while good in a straight line because it increases top speed—is extremely undesirable in corners because it decreases grip, and thus makes it harder to follow the car ahead. The turbulence is also far worse when following a car in a corner than in a straight line, much like following a boat on the edges of its wake rather than in the center, because it not only reduces downforce but can also make it harder to predict the behavior of the car.

Because no other racing cars produce as much dirty air while being as reliant on downforce to go fast around corners, the issue of dirty air is almost exclusively limited to Formula 1.

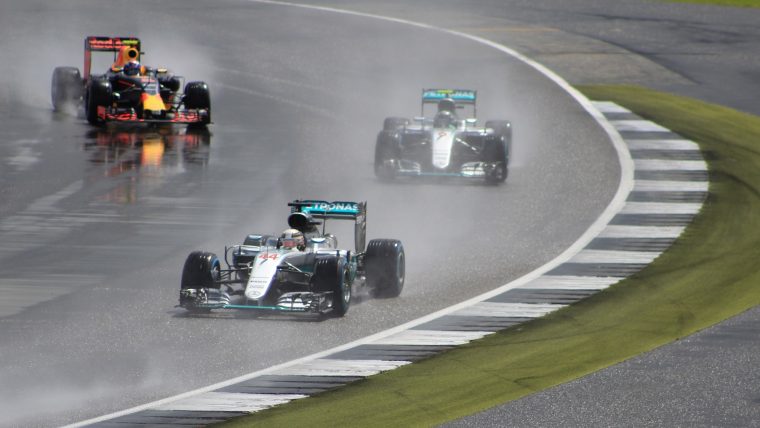

Following another F1 car can be tricky, and not just when it rains.

Photo: Joseph Petrassi

Kurt Verlin was born in France and lives in the United States. Throughout his life he was always told French was the language of romance, but it was English he fell in love with. He likes cats, music, cars, 30 Rock, Formula 1, and pretending to be a race car driver in simulators; but most of all, he just likes to write about it all. See more articles by Kurt.