In the ongoing debate over the future of mobility, electric vehicles (EVs) often win on paper but struggle on the road—and not for technical reasons. The issue lies less in their engines and more in the complexity of daily use, accessibility, and political strategy. Even the most efficient technologies are not immune to societal friction.

At the core of the argument is a physical reality that experts say should be hard to ignore: the electric motor is vastly more efficient than any combustion engine, including those powered by so-called e-fuels. Yet adoption remains sluggish, especially in regions where infrastructure and habits haven’t caught up. Behind these numbers, the conversation takes a political turn—with major automakers and member states pushing back against the 2035 combustion engine ban.

A Massive Gap In Efficiency From Lab To Road

In pure thermodynamic terms, the difference is striking. Electric motors convert around 70% of their energy into motion under real-world driving conditions. Combustion engines? Somewhere between 30 and 40%, even under optimal conditions. According to physicist Johannes Kückens, quoted in Der Standard, the figure drops drastically when synthetic fuels are added to the equation.

The issue with e-fuels isn’t just the engine itself—it’s the upstream energy cost. Producing synthetic fuels involves three highly energy-intensive steps: water electrolysis to make hydrogen, CO₂ capture from the air, and the chemical synthesis of liquid hydrocarbons. Each step introduces significant losses. Kückens notes that when everything is factored in, including the fuel’s journey from “wind to wheel,” a combustion vehicle powered by e-fuels uses just over 10% of the original renewable electricity.

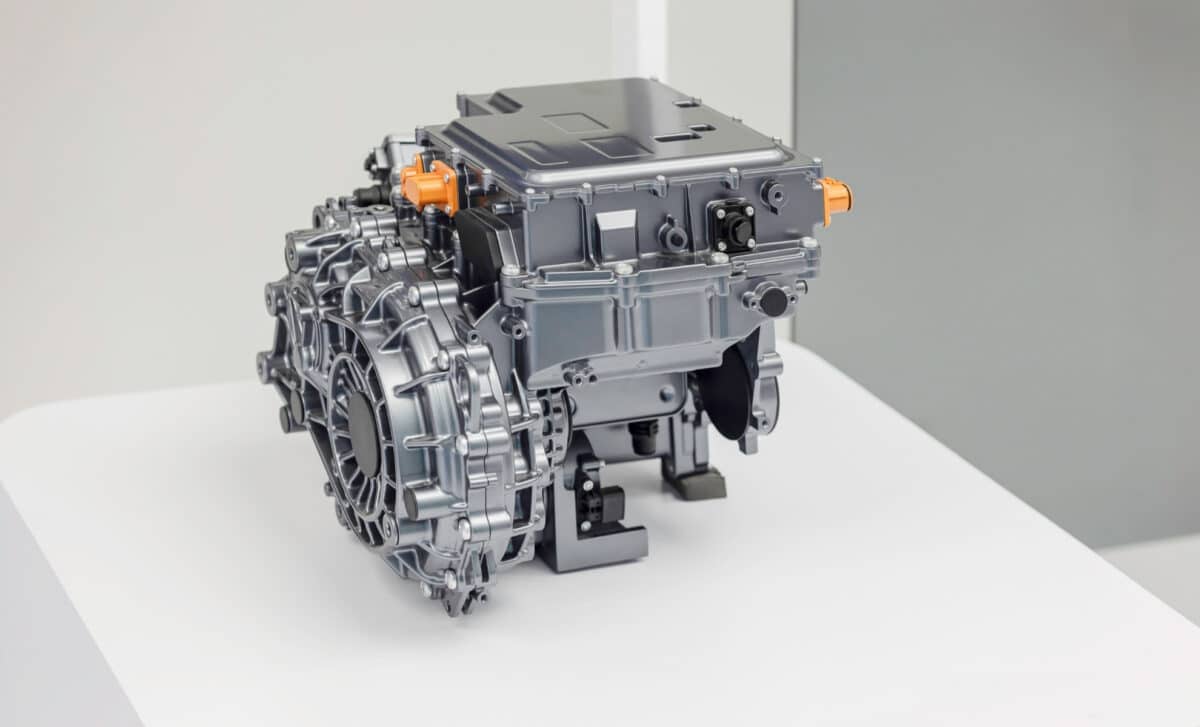

By comparison, an EV using the same amount of electricity can travel six times farther. And even against traditional gas or diesel engines, the electric car still comes out ahead—achieving roughly three times more range per kilowatt-hour. This technical advantage is amplified by the EV’s simplicity: only about 250 mechanical parts make up its motor, compared to around 1,500 in a conventional combustion engine.

The Problem Is Not Physics—it’s Usage

But the numbers alone haven’t tipped the scale. The real barriers lie elsewhere: in driving habits, expectations, and infrastructure. With a fuel-powered car, a driver can cover 800 to 1,000 kilometers on a full tank, no special planning required. For EVs, even the best models often require a stop every 300 to 400 kilometers, with charging pauses of 10 to 20 minutes—not ideal for spontaneous or long-distance travel.

This challenge deepens in dense urban areas. While EV ownership is easier for those with private charging stations, that isn’t an option for nearly 45% of French households, based on INSEE data. Public charging networks remain unevenly distributed, and access varies widely depending on location, housing type, and income.

Despite growing momentum—battery technology is advancing, European recycling systems are emerging, and new chemistries like LFP are reducing reliance on rare metals—EVs still only accounted for 17.5% of new car registrations in the EU as of June 2025. In fact, this share has dipped in some countries after subsidies expired, notably in Germany.

Public Resistance And Political Pushback Threaten The 2035 Deadline

Public opinion continues to diverge from official EU goals. In Germany, for example, nearly 67% of respondents oppose maintaining the current 2035 deadline to ban new combustion engines, while only 28% support it. At least seven EU member states have now called for a re-evaluation of the regulation, opening the door to exceptions or postponements.

These exceptions may include hybrid vehicles, plug-in hybrids, or cars with range extenders. Even though these solutions don’t match pure EVs in energy efficiency, they offer more flexibility and ease of use—making them more appealing to average drivers who value autonomy and simplicity.

The political pressure is not only coming from governments but also from parts of the German automotive industry, which continues to lobby for the integration of e-fuels and transitional technologies. The European Commission is reportedly considering loosening CO₂ targets, delaying the combustion engine ban by up to five years, and carving out exemptions for specific technologies.