Halloween has grown from a single, magical night into something of a season unto itself. Each year, we flock to theaters and couches to watch frightening cinema classics or the latest horror hits, visit haunted attractions for the sole purpose of being scared by strangers in masks, and gather around bonfires to regale one another with scary stories. Urban legends are perfect fodder for storytelling in the firelight, existing somewhere in the nebulous space between frighteningly plausible to completely unbelievable, yet almost uniformly surviving from having been passed between people at campfires or in email chains. They involve mythical creatures emerging from the shadows, sadistic killers who are making calls from within your own home, and, more recently, super tall and skinny guys in business suits who live in the woods and don’t have faces. Appropriate given how ingrained the urban legend is in the American identity, a great many involve people being menaced, terrified, and even killed in and around cars; the following are four of the best you can tell your easily-frightened friends this Halloween.

[wptab name=”The Killer in the Backseat”]

The Killer in the Backseat

Never before had “Total Eclipse of the Heart” been as terrifying as it was in the opening scene from Urban Legend

Photo: Sony Pictures Home Entertainment

According to Jan Harold Brunvand’s Encyclopedia of Urban Legends, this urban legend first known appearance in print was in a 1965 folklore journal under the title “Woman Trailed by Mysterious Car.” Three years later, folklorist Carlos Drake dubbed a similar tale “The Killer in the Back Seat” in a collection of texts put forth by students at Indiana University. Children of the 1990s are likely to recall interpretations of this story from one or both of two sources: as the tale “High Beams” in Alvin Schwartz’s perennial Scholastic Book Fair-favorite Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, or from the opening of the 1998 film Urban Legend, which starred a babyfaced Jared Leto who had not yet devolved into the self-important, used-condom-mailing torturer of castmates that most know and loathe today.

Per Schwartz’s version from Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, a young woman is making the eight-mile trek home to her family farm when she notices that she’s being tailed by a red pickup truck. She tries to shake the truck when it follows her long beyond the point of mere coincidence, but her pursuer only drives more aggressively in an effort to keep up with her. The truck then begins flashing its high beams, causing the girl to become overcome by panic.

When she pulls into her driveway, she runs into her home and yells out for her father to call the police. The pickup truck is not far behind, and the man driving it emerges from the cab holding a gun. Presumably, he just kind of, I dunno, stands out there with his gun for a while. When the police eventually show up to arrest him, he tells them that he is not the culprit they’re looking for despite his potential traffic violations. At his suggestion, the police officers check the back seat and find a man hiding behind the driver’s seat holding a knife.

The man in the red pickup, now vindicated from having been perceived as some kind of crazy nut (though, to be fair, it’s still entirely plausible that he is a crazy nut anyway given how these things tend to go), explains that he saw the man slip into the girl’s back seat at some point just before she left the basketball game she had been attending. Unable to warn her or call the police (keep in mind, cell phones were not a thing, and even if they were, it’s a safe bet that it would be dead or without service for narrative convenience), the truck driver decided to follow her and keep an eye out. Whenever the truck driver would flash his high beams, that was his way of warding off the assailant when he would rise up to overpower the driver.

As with any other urban legend, there are several variations. In some instances, the man in the truck is confronted not by the police but by an angry husband. Some versions replace the man in the truck with a gas station attendant who lures the driver away from her vehicle with a story about a counterfeit bill—or, as is the case with Brad Dourif’s character in Urban Legend, a declined credit card.

Whatever its form, this tale helped give rise to the notion of always checking the backseat before getting in the car—advice that inexplicably tends to go completely unheeded in most horror movies.

[/wptab]

[wptab name=”The Hook”]

The Hook

The killer from the 1997 film I Know What You Did Last Summer was inspired in part by “The Hook”

Photo: Columbia Pictures

No, this urban legend is not about the Blues Traveler song of the same name, though there is something about John Popper that is indisputably, innately terrifying.

Per Brunvand’s The Vanishing Hitchhiker: American Urban Legends and Their Meanings, variations of “The Hook” have been circulating since the 1950s. It arguably reached its apex on November 8th, 1960, when the following was published in the popular “Dear Abby” advice column:

Dear Abby: If you are interested in teenagers, you will print this story. I don’t know whether it’s true or not, but it doesn’t matter because it served its purpose for me: A fellow and his date pulled into their favorite “lovers’ lane” to listen to the radio and do a little necking. The music was interrupted by an announcer who said there was an escaped convict in the area who had served time for rape and robbery. He was described as having a hook instead of a right hand. The couple become frightened and drove away. When the boy took his girl home, he went around to open the car door for her. Then he saw—a hook on the door handle! I will never park to make out as long as I live. I hope this does the same for other kids.

—Jeanette

One has to ask: who exactly is locking up convicted felons and committers of violent crimes with their hook prostheses attached? Sounds like slip-shod work from a regular Barney Fife.

As with “High Beams,” this story reached a new generation some twenty years later when it appeared in Schwartz’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, accompanied by an appropriately ooky illustration of a drippy hook from artist and nightmare architect Stephen Gammell. In this interpretation, the boy—Donald—argues with his lady-friend that it is too early to go home and that a crazed lunatic with a hook for a hand and armed with a knife has no reason to impose himself on a couple of kids parked adjacent to the state prison from which he just escaped. Ultimately, he concedes, but not before stating, “Girls always are afraid of something,” which means that Donald here is maybe juuuust petulant and childish enough to be the current president. Then again, maybe that doesn’t actually line up since this Donald managed to get out of the car without saying anything overtly racist or insulting the widow of a fallen soldier or grading himself a 10 for driving the car without getting into a fiery crash or trying to rob transgendered people of their rights or having his confidants arrested and charged with conspiracy against the United States or

Of course, no amount of urban legends about escaped psychopaths could possibly deter the youth of America from the great national pastime of necking in the backseat of someone’s parents’ car. It may, however, have dissuaded youths from making out with the radio tuned to their local news stations, or from making out in close proximity to active (or abandoned) sanitariums. To that effect, maybe this campfire-tale-cum-email-chain-letter has saved a life or two throughout the years, or at least prevented the libido-killing circumstance of trying to remain caught up in a moment of passion with Rush Limbaugh’s bacon-fat-soaked voice gurgling through the speakers.

Though the hook-hand killer likely inspired the slicker-wearing lunatic in 1997’s I Know What You Did Last Summer (AKA Jennifer Love Hewitt Yelling “What Are You Waiting For?” Whilst Spinning Around in Circles in the Middle of the Road), its finest contribution comes to cinema comes in the form of this bit of Bill Murray magic:

How could the guy have a hook on his foot, you ask? I suppose you’ve never heard of famed serial slasher Hannibal McHookfut.

[/wptab]

[wptab name=”The Boyfriend’s Death”]

The Boyfriend’s Death

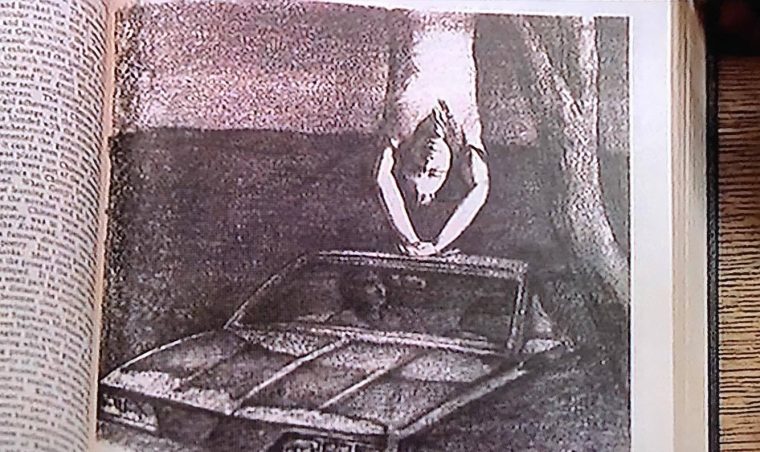

An illustration of “The Boyfriend’s Death” as seen briefly in Urban Legend

Photo: Sony Pictures Home Entertainment

Hmm. Another tale that became popular in the 1960s involving a young couple parked in a remote area and having their make-out session interrupted by an itinerant psychopath. It’s almost as if somebody back then really, really didn’t want young people exploring their sexual urges. After all, the next best thing to pushing abstinence-only sex education and defunding programs that provide actual sex education might just be attempting to convince young people that they’ll be slaughtered for being even remotely libidinous.

Unlike “The Hook” and “The Killer in the Backseat,” the killer is not thwarted at the end of “The Boyfriend’s Death.” Oh, honey, not at all. This should, to be fair, be pretty easily inferred from the title, which is “The Boyfriend’s Death.” Folks titling urban legends didn’t really have much concern for spoilers, ya know?

The premise is a similar one to that of “The Hook”: a young couple has found a quiet and romantic spot in a lovers’ lane—probably amidst a sea of bent, looming trees and plunged in complete darkness but for the glimmering light of a gibbous moon. It is strongly implied that whatever deed was the mutual objective has been done, as the incident that sets the story along its course is the inability to start the car when it has come time to leave. Like any ‘80s slasher flick, promiscuity is tantamount to doom.

The boy says that he will head back to the highway or the nearest gas station to get help, and he instructs his best gal to lock herself in the car and stay put. This could be put down to brutish machismo on its own, but variations leave cause for the girl to stay put. In some instances, there is a radio broadcast warning of an escaped mental patient, ala “The Hook.” In others, the girl refuses to walk with her boyfriend because she is wearing high-heeled shoes, because of course you would wear pumps to go hook up in the middle of the deep, dark woods.

Whatever the case, the girl stays put in the car for a long while without any sign of her boyfriend. Then she begins to hear a strange scratching sound on the roof of the car. The sounds persist as she panics her way through the dark night and into the dawn, when she is discovered by a state trooper. The officer gathers her up and leads her away from the car, imploring her not to look back.

But, as Brunvand writes in the Encyclopedia of Urban Legends, “Like Lot’s wife in the Biblical story of Sodom and Gomorrah, or like Orpheus leaving the underworld in the Greek myth, when told not to look back the girlfriend disobeys. Invariably in folk narratives of all kinds, taboos are broken.”

And when the girl looks back, she sees her boyfriend—dead, strung upside down from the branches of the tree hovering over his car, his fingernails scraping along the roof as he sways in the breeze. In some tellings, this causes the girl’s hair to go white from shock. In others, she loses her mind like so many Lovecraftian narrators and is whisked away to the asylum. In a shared universe that I just made up, that girl loses her hand to gangrene, has it replaced by a hook, escapes, and embarks on the path that leads her to become the legendary hook(wo)man.

Brunvand does note in his Encyclopedia of Urban Legends that “The Boyfriend’s Death,” interestingly, inverts the roles typical of stories that ward off teenagers from getting down by having the boyfriend be the one to suffer.

A useful survey of this whole interpretive approach to folklore appeared in 1993 in an issue of the journal Psychoanalytic Study of Society devoted to Alan Dundes. Included is a long essay introducing Dundes’s work by Professor Michael P. Carroll of the University of Western Ontario, followed by Carroll’s own study of “The Boyfriend’s Death,” in which he suggests that although females generally suffer more in real life than males do from teenage sexuality, “The Boyfriend’s Death,” which is most popular among young women, reverses the situation and punishes the boy instead. Since the boy cannot get pregnant, he is killed—significantly by being hanged and/or decapitated (i.e., punished at the neck for “necking”)—and then suspended upside down over the car as the final reversal in the story.

So, hey, I guess that’s something like equality maybe?

[/wptab]

[wptab name=”The Vanishing Hitchhiker”]

The Vanishing Hitchhiker

While “The Killer in the Backseat,” “The Hook,” and “The Boyfriend’s Death” are potentially byproducts of the post-war automobile boom of the 1950s, the tale of “The Vanishing Hitchhiker” can be traced back quite a bit farther, with Brunvand seeing “recognizable parallels in Korea, Tsarist Russia, among Chinese-Americans, Mormons, and Ozark mountaineers” dating as far back as the 1870s. Snopes.com notes similarities between the legend of the spectral hitcher and Acts 8:26-39 in the New Testament, in which Philip the Apostle goes on a chariot ride with an Ethiopian eunuch, baptizes him at a watering hole, and then disappears. Not sure that really qualifies as spooky, though.

While Brunvand’s 1981 book of the same name did a great deal to boost this urban legend into the main, it was a two-part article from Richard Beardsley and Rosalie Hankey in the California Folklore Quarterly published between 1942-43 that called attention to how widely spread the story was. Of 79 different accounts compiled from across the United States, the duo recognized four distinct versions of the tale.

Perhaps the most familiar variations are Beardsley and Hankey’s Versions A and C. The former is set in Berkeley, California, in 1934, and sees a young man out for a late-night drive spotting a winsome woman standing on the corner. Being a decent man, he offers her a ride, and she obliges by climbing into the backseat and providing her address. When the man arrives at what he presumes to be his passenger’s home, he turns around and finds that she has disappeared. Confused, he approaches the home and explains to the man who answers the door what had just taken place. The man at the door becomes frightened, explaining to the driver that the woman he picked up sounds very much like his fiancée, who was killed in an accident on that very same corner where the now-vanished woman had been standing.

Version C takes place in Salt Lake City in 1939, where a young man at a Christmas dance finds himself drawn to a mysterious gal wearing a white dress. After an evening of dancing, laughing, and staring longingly into one another’s eyes but feeling restrained by societal norms of the day, the boy offers to give the girl a ride home. She agrees, and when she steps out into the cold night without a coat, the ever-chivalrous young man drapes his coat over her shoulders. Inexplicably, the girl asks to stop at a cemetery along the way, a request the boy obliges despite being a pretty considerable red flag. She embarks into the cemetery alone and never emerges, leaving the boy to drive off sullenly. The next morning, he goes to the girl’s house and speaks with a woman there who explains that the girl he danced with had been the daughter of the home’s previous owners. She also tells him that the girl had been, ya know, dead for some time. The boy then has little other recourse but to head back to the cemetery, where he finds his dance partner’s grave—and his jacket, which had been neatly folded and placed on her headstone.

The bars outside Resurrection Cemetery are said to be burned by the touch of famed vanishing hitchhiker Resurrection Mary

Photo: Lakersnbulls91 at en.wikipedia

One of the most common vanishing hitchhikers is Resurrection Mary, who was said to have been struck down in a hit-and-run after leaving the Oh Henry Ballroom in Willow Springs, Illinois, and buried at the nearby Resurrection Cemetery. Sightings have persisted since the 1930s, with stories having Mary standing along Archer Avenue awaiting a ride back to her grave (ala Version A) or appearing at a nightclub in the southwest side of Chicago in search of a night’s entertainment and a ride home (ala Version C). Legend also says that Mary burned her handprints into the wrought iron fence encompassing the Resurrection Cemetery, though cemetery officials attributed the damage to a truck (because of course they did).

Though not among the versions uncovered by Beardsley and Hankey, arguably the best iteration of the vanishing hitchhiker legend turns the tables and puts the mysterious spirit at the wheel of a rig. Rather than simply disappear into thin air, she helpfully gives a tuxedo-wearing manchild to a truck stop to tell the assembled drivers that he had been sent by Large Marge.

[/wptab]

[end_wptabset]

Sources/Further Reading:

Brunvand, Jan Harold. The Vanishing Hitchhiker: American Urban Legends and Their Meanings. W.W. Norton & Company, 1981.

Brunvand, Jan Harold. Encyclopedia of Urban Legends. W.W. Norton & Company, 2002

Brunvand, Jan Harold. Encyclopedia of Urban Legends, Updated and Expanded Edition. ABC-CLIO, LLC., 2012.

Schwartz, Alvin, and Gammell, Stephen. Scary Stories Paperback Box Set: The Complete 3-Book Collection. HarperCollins Children’s Books, 2017.

Beardsley, Richard K., and Rosalie Hankey. “The Vanishing Hitchhiker.” California Folklore Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 4, 1942, pp. 303–335. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1495600.

Kyle S. Johnson lives in Cincinnati, a city known by many as “the Cincinnati of Southwest Ohio.” He enjoys professional wrestling, Halloween, and also other things. He has been writing for a while, and he plans to continue to write well into the future. See more articles by Kyle.