Originally designed for British military needs, this engine was both strange and incredibly effective, earning its place in naval vessels and trains during the mid-20th century.

Unlike traditional engines with a straightforward linear or V-shaped configuration, the Deltic’s triangular layout and double-opposed pistons made it look more like a mechanical puzzle than a machine. But behind its unusual appearance was a highly functional engineering solution developed in the post-war period, when Britain sought a safer and faster alternative to gasoline engines for its military fleet.

The story of the Deltic engine begins during World War II, when gasoline-powered torpedo boats posed serious safety risks due to their flammability. The British Admiralty turned to diesel as a safer option. Their search led to a German engine — the Junkers Jumo 204 — whose unique two-stroke, opposed-piston layout inspired British engineers. Napier, a British engine maker, had already licensed this design in 1933 and used it to develop its own version, called the Culverin. This set the stage for what would later become the Deltic.

A Design Unlike Anything Else

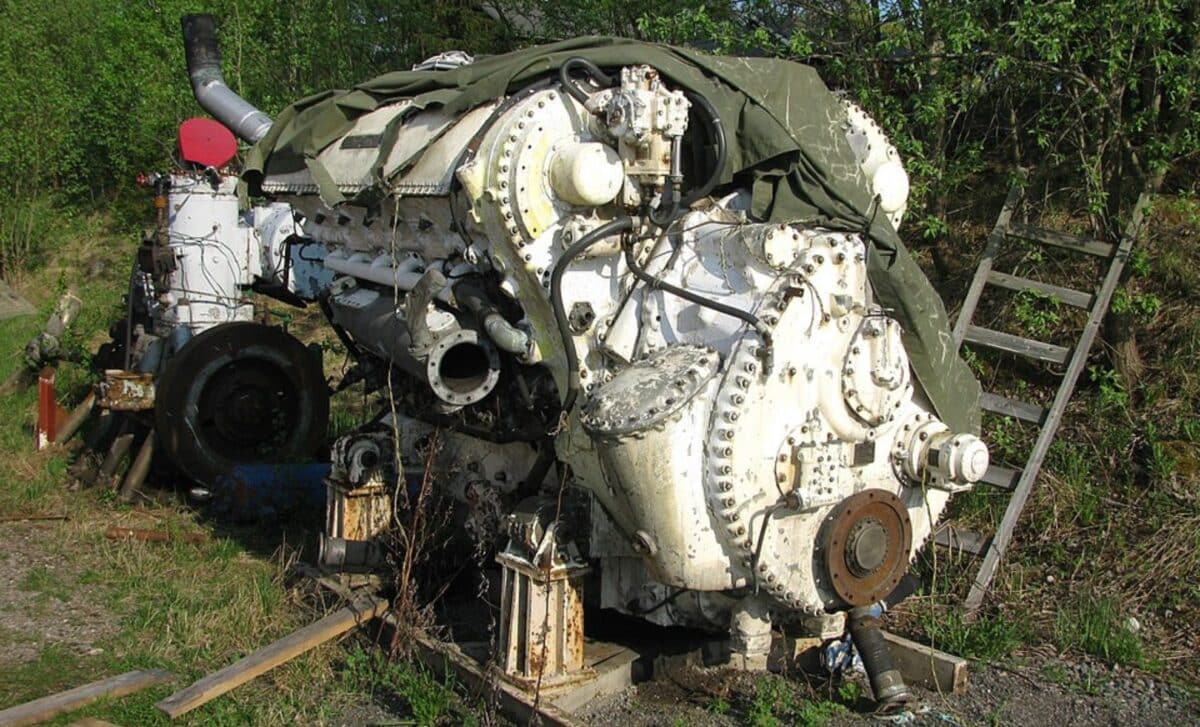

The final version of the Napier Deltic engine was completed in March 1950. According to Jalopnik, it featured three banks of six cylinders arranged in a triangle, each side of the triangle hosting a crankshaft. With two pistons per cylinder operating in opposition, the engine totaled 36 pistons and 18 cylinders — but due to the way certain components were counted, some sources refer to it as having 38 pistons.

Each crankshaft was synchronized with the others, with one turning in the opposite direction to solve timing and vibration issues. There were no cylinder heads. Instead, pistons moved toward each other within each cylinder, compressing air and fuel between them. Ports for exhaust and intake were cut directly into the cylinder walls, similar to how two-stroke engines function.

As reported by Supercar Blondie, the resulting engine measured 11 feet long, six feet wide, and seven feet high. It weighed around 8,725 pounds and displaced 88.3 liters. Despite its massive scale, it was engineered for high-speed performance and remarkable durability, capable of running 5,000 hours before needing a major overhaul.

Naval Power and Railway Performance

While it never powered any land vehicles, the Deltic engine proved effective in the settings it was designed for. Starting in the mid-1950s, it was used in British naval vessels and high-speed locomotives. The engine was powerful enough to drive trains across long distances without requiring frequent maintenance.

Napier even developed a smaller version called the Baby Deltic, a more compact 9-cylinder variant adapted for different operational needs. The original 18-cylinder Deltic, meanwhile, was refined over time to produce as much as 5,500 horsepower. It was particularly prominent in locomotives running between London and Edinburgh, serving as a workhorse for British Rail’s fast passenger service.

For a brief period, the Deltic engine even made its way to the United States, where it was used in equipment operated by the New York City Fire Department. Its unusual design demanded specific and careful maintenance, but when properly serviced, the engine performed reliably under tough conditions.

The End of the Line and Surviving Legacy

As newer technologies emerged, the Deltic’s reign gradually came to an end. By 1978, the rise of high-speed electric trains was making the engine obsolete. The final run of a Deltic-powered locomotive took place in January 1982, on a journey from King’s Cross Station in London to Edinburgh. Only 22 Deltic locomotives were ever built — and just six remain today.

Three of these surviving engines are now preserved by the Deltic Preservation Society, a group dedicated to maintaining and showcasing these historical machines. The engine’s strange design and performance history have kept it alive in the minds of engineers and train enthusiasts. While it no longer serves an active role in transportation, its legacy continues through museum displays and enthusiast communities.